They gather to talk about a topic most would rather avoid.

For some, this may be the first time they've talked about it — the impact on themselves, their family, their friends and co-workers, anyone who loves them. The pain, the guilt — maybe even the anger that it's gone so far. For others, it will be the first time they begin to get a sense of the damage it can do to those who are affected.

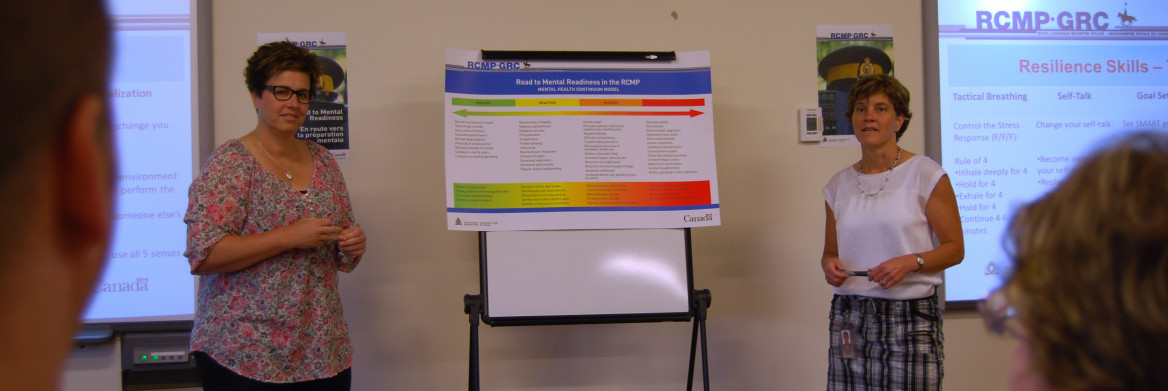

RCMP Mental Health Strategy

In addition to the Road to Mental Readiness program, the strategy includes:

Self-awareness tool

A colour-coded chart listing possible signs and behaviours for various states on the spectrum of mental wellness.

My Mental Health Care package

Information for employees to recognize signs of mental illness and to know when to seek help. It also highlights programs, services and contacts available to deal with mental illness.

Peer-to-peer co-ordinators

Provide a useful link between employees and the range of services available to the RCMP.

Tool kit for managers

Designed to help employees perform well at work and to take care of themselves.

They and their colleagues are gathered for a four-hour workshop that could change their lives, or change how they view some of those around them. There will be "aha" moments, there may be tears. There will be honesty — and compassion. And maybe, hopefully, understanding.

It's in a nondescript classroom, or a briefing room, or a lunch room, in a Royal Canadian Mounted Police building anywhere in New Brunswick. About two dozen people gather to talk about a subject few are comfortable discussing — mental illness.

It is one of dozens of sessions that have been held by New Brunswick RCMP as part of a two-year pilot of Road to Mental Readiness (R2MR), a program that recently received full endorsement by the RCMP at the national level. It will be rolled out across the country this year as mandatory training for all employees.

"Work-related stress and mental illness are real issues for both sworn and civilian employees and one that we take very seriously," says A/Commr. Gilles Moreau, the force's national mental health champion. "It's important for employees to know that there is no stigma associated with coming forward and acknowledging that something they've experienced on the job, or at home, is affecting their mental health."

Last year, the RCMP announced its five-year mental health strategy, which outlines initiatives to educate, reduce stigma and streamline policies to better identify mental health issues and provide support to those who find themselves struggling due to stress or mental illness.

Building resilience

The R2MR is intended to raise awareness about mental health and how to maintain mental resilience in a healthy and positive way.

New Brunswick RCMP partnered with the Department of National Defence in 2012 to adapt its R2MR program into a workshop for RCMP employees.

"It focuses on promoting long-term positive mental health outcomes for all employees, with the goal of better preparing us to navigate some of the challenges of a career in law enforcement," says Sgt. Liane Vail, who developed and led the pilot.

At the core of the R2MR is the mental health colour-coded continuum — a scale that outlines the behaviours seen in people at four states of mental wellness:

- Healthy (green) — examples include normal mood fluctuations, good attitude, good performance, physical and social activity;

- Reacting (yellow) — examples include irritability, teariness, sleeplessness, decreased activity, regular but controlled substance use;

- Injured (orange) — examples include anger, hopelessness, negativity, withdrawal, hard-to-control substance use; and

- Ill (red) — examples include depression, suicidal thoughts, inability to perform duties or concentrate, isolation at home, substance addiction.

Seeing the signs

The premise is that if employees see themselves or a colleague moving away from green into one of the other stages, there are actions that can be taken to return to healthy.

There are two instructors for each workshop — one is a peer facilitator and the other is a mental health professional, such as a psychologist, psychological nurse or social worker.

Sgt. Scott Sawyer is a peer facilitator at New Brunswick RCMP headquarters in Fredericton, N.B. As someone who has chronic post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), he says there is great value in the program.

"I was in the orange and red for several years," he says, using the R2MR colour codes for injured and ill. "If I'd had that type of training before, I may have been able to recognize the signs earlier and prevent a total burn-out, so I think it's pretty important training for everyone."

His "aha" moment was learning about how the brain works in response to stress — either extreme or long-term. Specifically, it was the role of the amygdala, located in the brain's temporal lobes, and its role in the fear, flight or freeze response to traumatic events or highly stressful situations that proved revolutionary for Sawyer.

"When you understand, you can do something about it," he says. "You don't have to just react based on what the amygdala dictates. You learn how stress works, what you can do about it and how to process your thoughts."

And as a manager, he is doing things differently as a result of the new perspective R2MR gave him.

"I take a totally different approach to mental health issues now and I can catch the signs quicker to get people back on the road to recovery faster," he says.

Protective coping

The workshop has four modules: mental health in the RCMP, the stress reaction, resilience skills and resources at work. It teaches participants that:

- stress is a natural body response and can be positive;

- the body's response to high stress is instinctual to protect it from danger, and occurs without rational thought;

- too much stress for too long can be harmful; and,

- the key is to understand and manage stress, not try to prevent it.

Critical in the training is teaching protective coping skills, says Dr. Julie Devlin, a psychologist with the Operational Stress Injury (OSI) Clinic in Fredericton and a R2MR facilitator.

A study she conducted with Dalhousie University and the University of New Brunswick on the prevalence of OSIs and protective factors supports the approach to building resiliency taught in the R2MR.

"I think it really has potential to make a big difference for a lot of RCMP employees," she says. "It teaches how to take control of how you respond to things happening around you."

Making a difference

And Devlin says she finds the experience very gratifying.

"It shows that you can experience trauma and come through it," she says. "It's a really rewarding experience both professionally and personally because I see people struggling, and then get to watch them learn about the tools to help cope and the help that is offered by the RCMP."

Claire Gibson, a civilian analyst who has been with the RCMP for 13 years, is a peer facilitator. For her, one of the key elements of the program is that not one type of stress is more valid than another.

"Operational stressors, work stressors, or personal life stressors — they are all treated the same," says Gibson.

And she says she sees a change in her colleagues since the program has been introduced in New Brunswick.

"It has normalized the idea of mental health challenges and it attacks the stigma," she says. "It's a good sign that people are starting to have a dialogue about it."

For her, it's the moments when she sees that people are getting it that stand out most.

"They see where they are on the R2MR continuum and know where to seek help if they need it," she says.

Pairing peers with professionals

The R2MR will be launched across the country with a series of training sessions for both peer facilitators and mental health specialists. Having both the facilitator and the practitioner is critical, Vail says.

"The peer brings the credibility but the evidence is from the mental health specialists," she says. "The peer can say that this is what happens and the specialist can say that this is why."

Devlin has an outside vantage point of the program and the work the RCMP is doing in the area of mental health. She describes it as a "groundswell" since the launch of the mental health strategy.

"There's been a huge change and shift in addressing mental health issues in the last year and a half," she says, noting that they are seeing more RCMP members at her clinic now, including some on active duty — something many needing help are reluctant to do.

"It's not necessarily that more people are ill," she says. "But a contributing factor could be that more feel like the stigma is lifting and it is okay to need help."